|

A Total Eclipse of the Sun,

image from Wikipedia |

On July 11th, 1991 I experienced a total solar eclipse of the sun at the ruins of Yagul in Oaxaca Mexico. Perched high above the valley floor, I remember seeing the shadow sweeping over the earth at totality like the flash of a giant a raven's wing travelling at 1000+ mph. Cocks began to crow, dogs frantically barked and birds nervously returned to their nests. Bright stars and planets suddenly appeared in the sky; the air temperature dropped. Looking up, I saw giant curls of solar flares ringing a black sun face. It was a cosmic struggle between forces of light and the forces of dark; a battle between the powers of order and chaos. All was completely beyond my control. No wonder the Maya scribes sought understand the cosmic order of the skies; an order that arises out of the great mystery of the universe, the

mysterium tremendum that partly reveals itself through the intricate machinations of the Maya calendar, its priestly divinations and mathematic calculus.

In the future total solar eclipse will pass over the United States on April 8th 2024. I thought I would celebrate the celestial show by relating how ancient Maya scribes depicted a similar event in their Classic art and inscriptions and discuss a rediscovered record of a possible eclipse recording at the Olmec site of Tres Zapotes.

|

| Drawing by Peter Mathews |

The ancient Maya recorded an eclipse for the day 9.17.19.13.16 5 Kib 14 Ch'en a total solar eclipse appeared over Southern Mexico. The local ruler Yax Bahlam at the Chiapa site of Santa Elena/Poco Winik recorded the momentous occasion on Stela 3 using a hieroglyph that specifically depicts the dramatic moment when darkness cloaked the sun:

The hieroglyph contains a K'IN or sun glyph in the centre that is flanked by two 'winged' elements. The round circles at the base of the glyph may indicate a -ma syllable for a phonetic compliment. The central glyph is a four-lobed portrait of sun or K'IN glyph with a central dot. A circular cartouche frames this sun portrait. The four-lobed partitions echo the four divisions/four solstice points of the year along the horizon created by the annual solar trek. The glyph acts a mandala-like cosmogram of the Maya universe with four sun points united by a fifth central point relating to solar zenith (Girard 1995:6). This connection between the sun and the numeral four is verified by Maya scribes with their rendering of number four as a portrait of the Sun God:

|

| Drawing of the Number Four after Thompson 1971 Fig. 24 |

The god is typically depicted with a fat protruding nose, a buck-tooth incisor and a squinty crossed eyed stare. The face can carry a K'IN four-lobed cosmogram on its cheek. Caution 2024 eclipse revelers! Take a warning from the solar malady: you too will become cross-eyed by staring too long at the sun!

The eclipse glyph is also flanked by 'winged' liked elements that are inset with circular cartouches and crossed bands. What are we to make of these attributes? The crossed bands are found commonly in skybands that indicate a celestial realm or border:

|

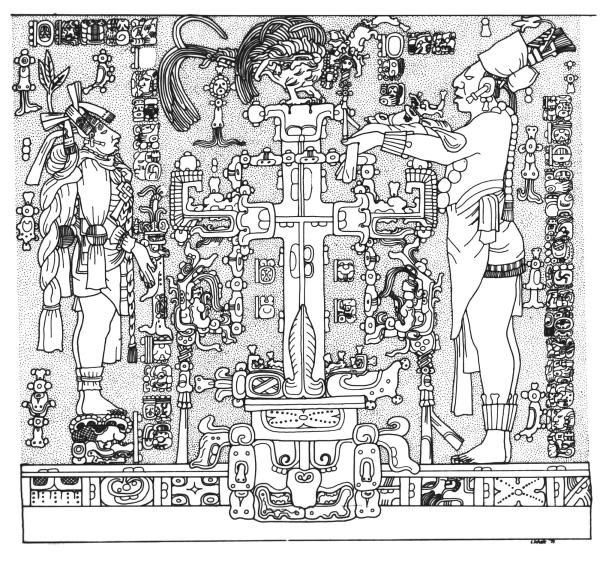

Sky Bands from Janab Pakal's Sarcophagus Lid, Drawing by Merle Greene Robertson

|

Other easily recognisable celestial signs inset in the Palenque star bands above are K'IN (sun), AKB'AL (darkness), CHAN (sky), EK' (star) and UH (moon). Some scholars liken the crossed bands to the cross beams in the roof of a traditional Maya house since the bands often carry TE' signs indicating the poles are made of wood (also the frames of the starbands themselves carry the same TE' markings). So the roof of heaven is conceptualized like the framed roof of a house.

The same skybands take on the animated form of a celestial bird as seen from Palenque House E (this CHAN bird is also serves as the zoomorphic variant for the BAK'TUN or PIK sign):

|

| The Celestial Bird Drawing By Linda Schele |

It is very common to see celestial bird wings morphing into the sky bands, so there is a definite connection between bird wing and sky in the scribal mind. The same might be said for the Santa Elena eclipse glyph. It is possible that the sun glyph is being cloaked by a pair of stylized bird wings but since this glyphic collocation is so rare, it is difficult to make a firm identification. Other celestial birds like the Principle Bird Deity (AKA in the Post Classic as Seven Macaw from the Popol Vuh) show AKB'AL and K'IN signs emblazoned under its wing. A great example is found on Kerr Vase K3105c and K3105e:

|

| The Principle Bird Deity on K3105c. Photo by Justin Kerr |

|

| The Principle Bird Deity on K3105e Photo by Justin Kerr |

In this instance is the left wing cloaking the night and the right wing cloaking the sun or both wings hiding a crescent moon shield? The Popol Vuh relates how the pride of Seven Macaw hide the sun and moon:

. . . there was one who puffed himself up named Seven Macaw. There was sky and earth, but the faces of the sun and the moon were dim. He therefore declared himself to be the bright sign . . . "I am great. I dwell above the heads of the people who have been framed and shaped. I am their Sun. I am also their light. And I am Also their moon . . . (translated by Allen J. Christenson 2003: 91-92) .

Such a vainglorious bird. But those of you who own and care for Macaws, know how boisterous and cocky these birds can be!

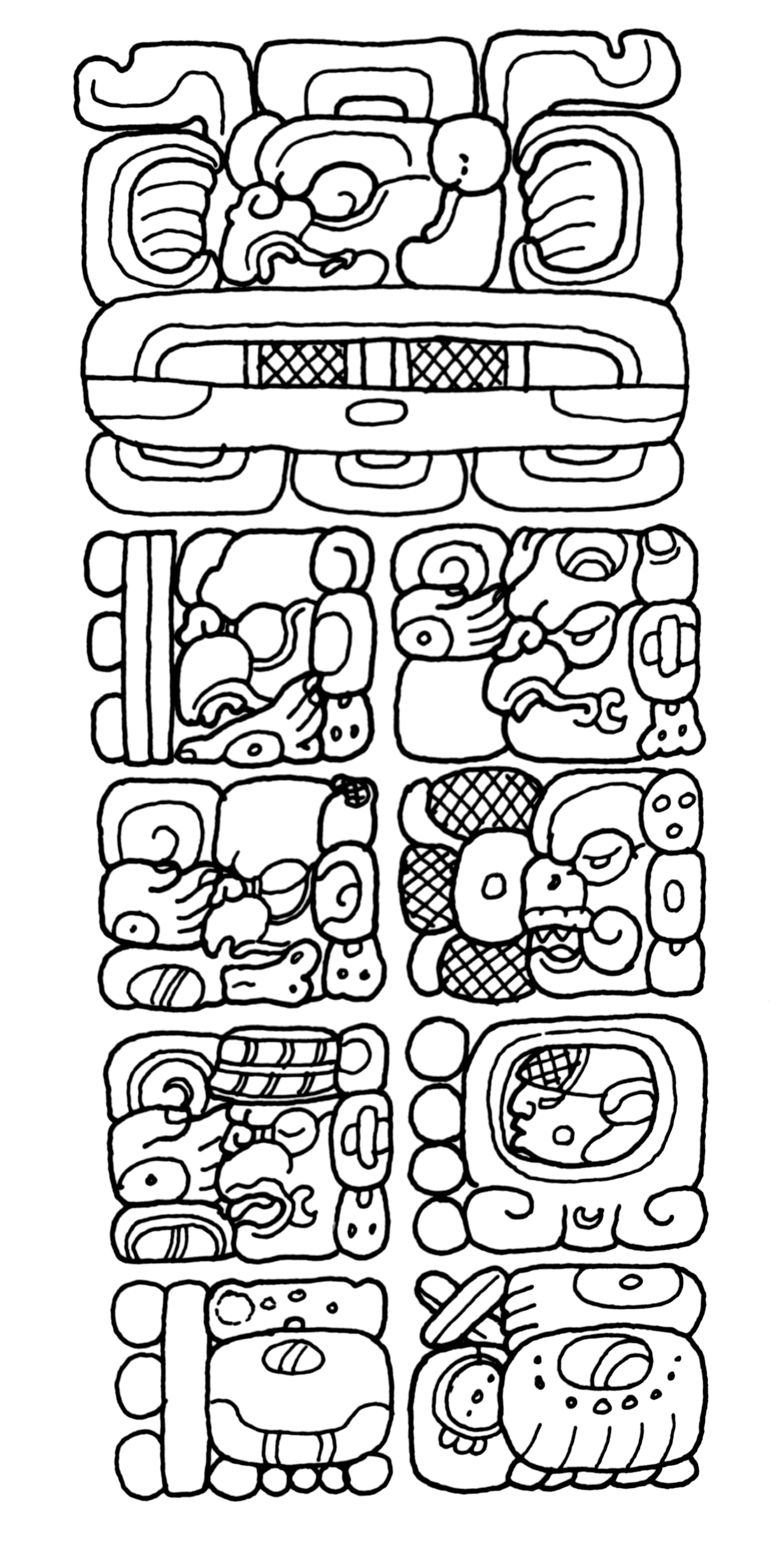

Eclipse glyphs similar to the Santa Elena glyph are found in the Dresden Codex (pages 51-58):

|

| Dresden Codex, page 54b Block D2 |

In the codex the eclipse glyph is a bit scaled down from the Santa Elena example but still maintains the central K'IN portrait and is flanked by white and black 'wings' that infer the dramatic shift from of light to dark. The Dresden pages show not only several eclipse glyphs but large animated scenes of eclipsed sun or moon hanging from star bands:

|

| Dresden Codex, page 57b |

On page 57b, the codex shows a barbed serpent is about to take a bite out of the sun. The image illustrates what the Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel records (Translator Ralph Roys 1967:76):

. . . then the face of the sun was eaten;

then the face of the sun was darkened;

then its face was darkened . . .

A similar image on page 56b has added graphics:

|

| Dresden Codex, page 56b |

Not only is the sun being bitten into by the serpent, but it is also pierced by two barbed bone needles and the 'winged' elements are substituted with black and white optic-looking (your guess is as good as mine here) body parts? Are the bumps on the rim renditions of Baily’s Beads or 'jewels' of sunlight appearing along the rim of the eclipse just before Totality? What is obvious is that the Sun God is bitten and punctured and his shining face darkened.

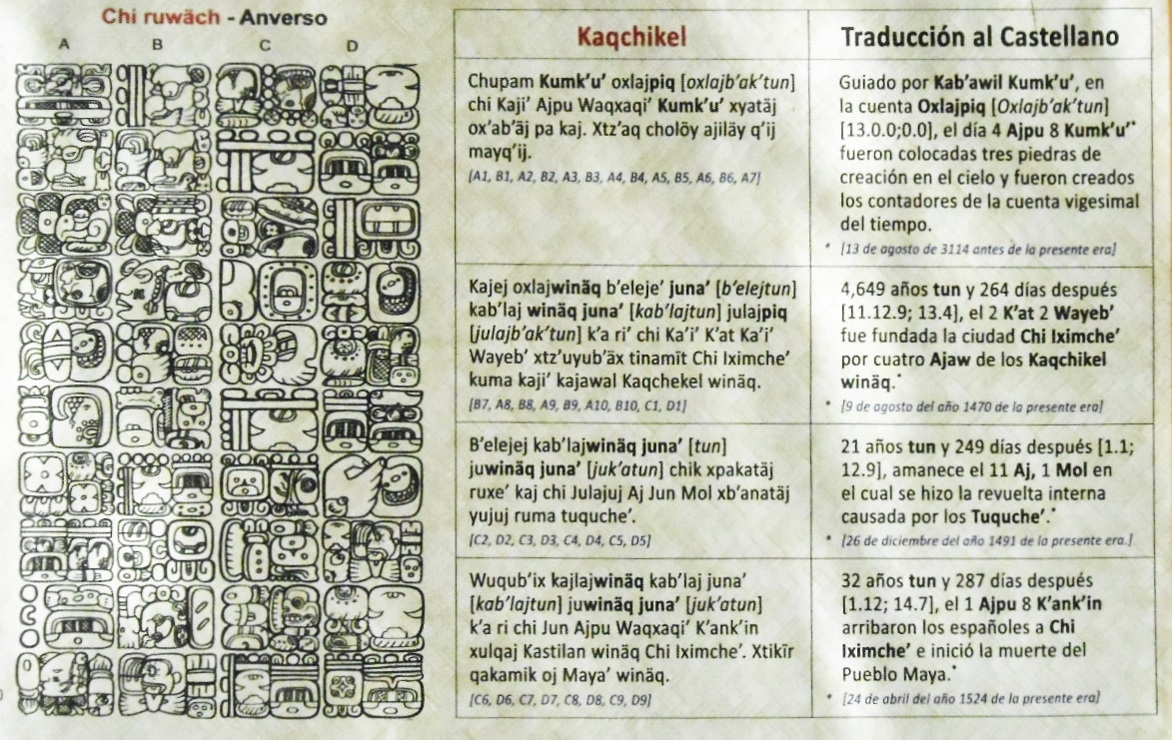

I will end with a possible eclipse recording on Stela C, from the Late Olmec site of Tres Zapotes with a Long Count date of (584285 GMT) 7.16.6.16.18. 6 Etznab 1 Wo = September 3, 32 B.C.E. Interestingly the monument looks like it is recording a 7 Etznab rather than a calculated 6 Etznab and so it could be signalling the period when the Tzolk'in or the Haab are not yet in sync. with one another. As Maelstrom (1997: 140-142) states the monument may record a stunning dawn eclipse that:

. . . is one whose path of of centrality passed right over the Olmec ceremonial centre of Tres Zapotes at dawn on the morning of August 31, 32 B.C. A more frightening celestial event can scarcely be imagined, for the sun rose totally out of the Gulf of Mexico totally black except for a ring of light around its outer edges. Oppolzer described it as an annular, or ringlike, eclipse, and subsequent calculations at the US Naval Observatory (p.c.). Surley, a 'day without a sunrise' is not likely to have gone unnoticed by the Olmecs!" (Malmstrom 1997:142)

A dawn annular eclipse (when the moon covers the Sun's center, but leaves the sun's visible outer edges exposed to form a “ring of fire”) over the Gulf of Mexico would have looked something like this:

|

| A Dawn Annular Eclipse |

What a frightening ring of fire rising out of the sea! Take note that the recorded Long Count date is offset 2-3 days from the actual eclipse date, so a direct correspondence is not present and is only approximate. There is more than just the date to suggest an eclipse connection. Although Malmstrom discusses the Long Count on Stela C in depth, he does not describe the iconography the reverse of the monument:

|

Tres Zapotes Stela 3, Front and Back,

image from http://www.elministerio.org.mx

|

There is a low relief carving of what seems to be of an anthropomorphized solar disk rising out the cleaved forehead of an Olmec-like god, very much in the same way the sun sign for east rises above the head of the aquatic god GI from the Maya Classic Period. Also note the wings of a giant bird cloaking the head of the figure, wings that are reminiscent of Seven Macaw outstretch feathers hiding the sun and the moon. The parallels to Classic Maya imagery are striking indeed. Is this an animated portrait of an eclipsed Olmec Sun God? There is a lot more iconography on Stela C to discern and I welcome more input from readers.

Good luck to those viewing the 2024 total solar eclipse

It is 'Totality or Bust!

Best,

Carl

Works Cited

Christenson, Allen J. 2003 Popol Vuh The Sacred Book Of The Maya. Winchester, UK and New

York: O Books.

Girard, Raphael 1995 People Of The Chan. Bennett Preble, translator. Chino Valley, Arizona: Continuum Foundation.

Malmström, Vincent H. (continued) 1997 Cycles of the Sun, Mysteries of the Moon: The Calendar in Mesoamerican Civilization. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Roys, Ralph L. 1967 The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel. The Civilization of The American Indian Series. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press.

Thompson, J. Eric S. 1971 Maya Hieroglyphic Writing: An Introduction. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.